Unpacking Chinese financing of Pakistan’s “dream” power plant

By Liu Shuang, Program Director, Low Carbon Economic Growth Program, Energy Foundation China

There has been much discussion about China’s involvement in coal projects overseas. Critics point to the tremendous carbon footprint it may create, and call for a change in the practice. Analyses have highlighted the complicated dynamics that enable the continued build-up of coal fired power capacities around the developing world, against the stern warning of climate scientists.

Within that complex dynamics, financing is one central piece of the puzzle that is often poorly understood. Due to intrinsic difficulties in gaining access to information about how financial actors (especially Chinese ones) operate, presenting an accurate picture of key financial components at project level proves to be challenging.

This blog tries to shed some light on Chinese financed coal-fired power plant, by using a “strawman case” built out of publicly available information.

The case in point is the Engro Thar Block II (ETBII) project in Pakistan’s Sindh province, one of the key coal power projects listed under the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). As a major destination of Chinese coal investments globally, Pakistan provides a good observatory point to understand why coal projects along the Belt and Road continue to get funded by Chinese lenders.

Engro Thar Block II 2×330MW Coal fired Power Plant TEL 1×330MW Mine Mouth Lignite Fired Power Project at Thar Block-II, Sindh, Pakistan. Source: CPEC Website

“The Thar dream”

Ever since the discovery of the massive coal reserve in Thar in 1991, a desert area 500 kilometers to the east of Karachi, the anticipation of developing Pakistan’s indigenous source of energy has captured the imagination of the nation. The reserve is estimated to comprise 175 billion tons of lignite coal. Unlocking a fraction of it would be sufficient to power the entire country, which, to this date, still heavily relies on imported fuel oil for its electricity demand. But technological barriers had thwarted attempts to tap the resource in the past. And due to concern with climate change impacts, the World Bank withdrew its support for the endeavor in 2009, leaving the project in financial uncertainties for a few years.

The entry of Engro, one of Pakistan’s largest private energy conglomerates, breathed life into the project. But the prospect of developing the Thar minefield really improved after China got on board. In 2014, Engro Thar Coal-fired Power Plant (660 MW) was listed under the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). And the year after, a consortium of Chinese finance institutions committed to fund the project, enabling the project to achieve financial closure in April, 2016. According to CPEC’s official project registry, the Engro Thar Block II project is a combination of coal mining and mine-mouth power generation, with the first phase of the coal-fired power plant consisting of two 330MW units.

Engro’s official website celebrated the project as a “significant feat”, marking “a new era for energy security in Pakistan and brings with it the realization of the Thar dream.”

Chinese actors

The project illustrates a typical financing structure that is increasingly common along the Belt and Road.

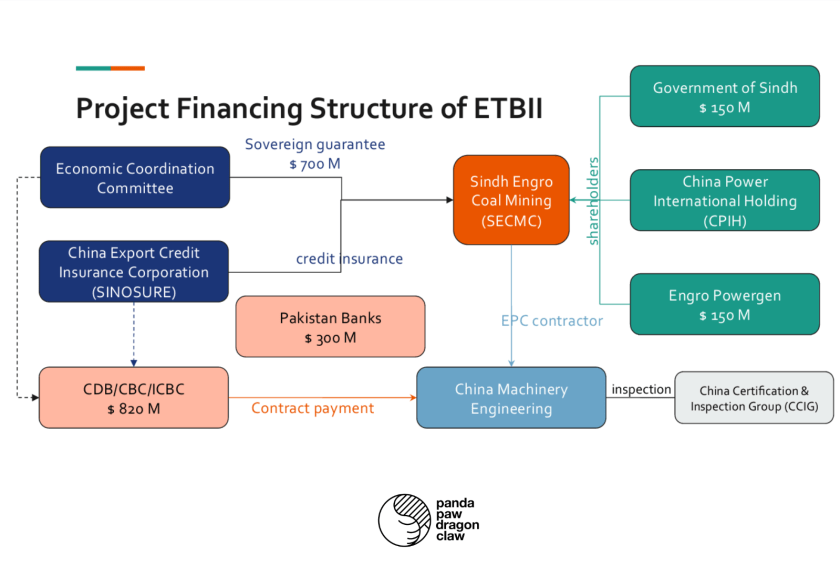

At least four categories of Chinese actors are involved in this case:

Lender : China Development Bank (CDB), Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), Construction Bank of China (CBC)

Credit insurance: Sinosure

Construction company (EPC contractor): China Machinery Engineering (CMEC)

Project developer: Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company (SECMC, with China Power International Holding and CMEC as shareholders)

As in many other similar China-financed projects, the structure features one Chinese policy bank (either CDB or the Export-Import Bank of China), two Chinese commercial banks and Sinosure. The arrangement helps spread financial risks across multiple Chinese players. While players such as CDB has attracted wide attention as one of China’s financial engines powering the Belt and Road Initiative, other key players have managed to stay out of the spotlight. One of them is China Export & Credit Insurance Corporation (Sinosure), whose involvement in such deals can often tip the balance between go and no-go.

Sinosure engages in a business known as “policy insurance”, non-profit oriented insurance bankrolled by China’s treasury, with the aim of promoting the country’s export and overseas investments. In a project like ETBII, Sinosure provides an Export Buyer’s Credit Insurance to the Chinese financial consortium against the risk of repayment delay or failure due to political or commercial reasons. For a range of risks from war to contract breach, the company offers a maximal 95% insured percentage. The safety net is critical in markets with high uncertainty and gives Chinese companies a considerable edge. Despite the seemingly bottomless “pockets” of Chinese policy banks and state-owned commercial banks, whether Sinosure is on board usually accounts for “50-60% of the weight” in their decision making, according to those familiar with the matter. And Chinese actors don’t even have much choice. Alternatives to Sinosure, commercial insurance companies or foreign insurers, are much less desirable for their high charges. Sinosure’s influence in deciding China’s overseas energy footprint cannot be underappreciated.

Even though on paper Sinosure may maintain an “agnostic” approach to the types of energy projects it insures, be they coal-fired or renewable, other project features can tilt it more toward coal. Guarantee from a project’s host country government matters to an insurer. Large fossil fuel projects, in this regard, usually have better access to state support than renewable energy projects much smaller in scale. Smaller project size also means a lower “financial threshold” of entry, attracting developers that, to insurers, are intrinsically riskier. Large fossil fuel projects may also leave behind more valuable fixed assets than renewable projects in occasion of a default, an important consideration for insurers. All those non-climate related factors may make Sinosure more inclined toward projects like ETBII.

A bankable PPA

In any major power project that involves financing from international lenders, the Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) often ranks as the most important contractual component of the deal. On the surface, a PPA is merely an instrument that facilitates the sale and purchase of electricity. But more importantly, for most power projects, payment from the buyer under the PPA constitutes the only revenue stream for the project company to repay its loans. The negotiation and set-up of a PPA would often decide if a project is considered “bankable” to potential lenders.

The Pakistani authority has more or less standardized the PPAs of coal power projects, making them acceptable for international financiers. In a 2016 presentation by Pakistan’s Private Power and Infrastructure Board (PPIB), a government body that facilitates investments into the country’s power sector, it boasts government guarantee of power purchaser obligations, attractive Return on Equity (ROE), tariff indexation against inflation and government assurance of foreign currency conversion as terms that would sweeten a power deal for foreign investors. Most, if not all, of those elements will end up in a project PPA.

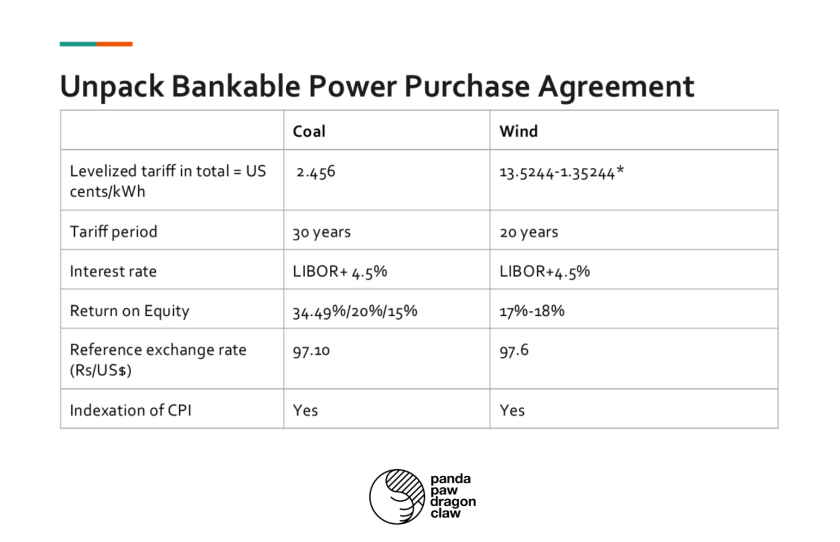

Based on the information published by Pakistan’s National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA), we could get a glimpse of the key components of the PPA for ETBII. The following chart lists those components and juxtaposes them with equivalent PPAs of wind power projects in Pakistan for reference.

* A selection of multiple wind energy PPAs from the NEPRA website is used here for reference purpose

Beyond the fact that a coal power PPA usually features a relatively low electricity tariff, which is highly valued by Pakistan’s policy makers and regulators that put “affordability” of electricity at the center, the PPA also caters to the needs of other key stakeholders in the deal. From a lender’s point of view, the PPA’s tariff formula incorporates debt service considerations of the project, based on a standard interest rate (London Inter Bank Offer Rate plus 450 basis points) for foreign currency loans. In addition, it also promises an over 30% Return on Equity for the project’s sponsors (i.e. shareholders), which is higher than what’s typically factored in in PPAs of other similar projects (15%-20%).

The PPA represents a different kind of product that is being promoted along the Belt and Road: the knowhow of setting up financial frameworks of projects fundable by Chinese financial institutions. As Chinese banks and companies take leading roles in overseas power projects, they share their expertise with host countries, showing them how to make projects work. This is something much less tangible than the infrastructure projects ended up being built, but no less important.

The enabling environment

Chinese financing can only be materialized into projects with the help of enabling investment and regulatory frameworks in Pakistan, co-created by a host of government agencies. The bonding of the two elements releases “energy” that propels Belt and Road power projects forward.

In the ETBII case, beyond PPIB support of the project, endorsement statements were provided by the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Resources and the Government of Sindh in support of the project, quoting energy security and the use of “indigenous resources” as main reasons; the province’s Environmental Protection Agency issued a No Objection Certificate, with no climate considerations included.

For those with a view to contain and even reverse the “chemical reaction”, understanding both the financing element and the enabling element will better prepare them for engagement and intervention. The strawman case is not meant to depict a complete picture. Yet the snapshot it creates should contribute to the mapping of key players and their interactions that illuminate the way ahead.

Source: https://pandapawdragonclaw.blog